What Women Need to Know About Sleep Apnea and Brain Health (Interview)

Maureen Garry: Hello and welcome to the Female Brain Summit. I’m your host, Maureen Garry. Thanks for joining us for this session where we’re going to talk to a dentist who is specializing not only in oral health, but in sleep along with his dental work.

Dr. Mark Burhenne had things happening in his own family he didn’t really realize. He didn’t know that his own family had sleep apnea issues. And so, the more he learned about that, the more interested he got—and the more he started being able to take that knowledge into his patient population and help his patients with their sleep.

Sleep is so fundamental, as we all know. And now, we’re going to learn from a different perspective about how we can improve our sleep. Dr. Burhenne has some really, really interesting information about the structure of our mouth—many, many different things we haven’t thought about before.

So, we’re just going to ask him a bunch of questions. We’re going to dive into sleep and sleep apnea and obstructive sleep disorders from the perspective of a dentist.

So, Dr. Mark Burhenne, welcome to the summit!

Dr. Mark Burhenne: Thanks! Thanks for having me on the summit.

Maureen: It’s wonderful to have you! You’re a fascinating person. We got to talk a little bit offline, but you started off with your family’s sleep issues. So, just give us a couple of minutes of background. How did you even start diving into sleep?

Dr. B: Sure! Well, again, as usual, it starts off with a personal story. When it happens to you, you become very interested and very concerned. And I did!

We were dropping my eldest off at college. I guess I’ve put us in the same hotel room for the first time in a long time. And I literally woke up with three of my daughters just hitting me with pillows in the morning saying, “Dad, that was just too much last night! You really need to stop snoring.”

Of course, at that time, I knew nothing about sleep apnea. And it took us about a few weeks to realize that it was a concern.

It was really a conversation I had that morning at the Continental Breakfast in the hotel with someone that had overheard my wife and I talking about snoring. He leaned over and he said, “Listen, snoring is serious stuff.”

He was just probably a truck driver or someone. He’s telling me something that I didn’t know about that I ended up telling everyone else about—that snoring is a serious thing.

It’s not funny. It’s not laughable. It’s not cute when your child snores or when grandpa snores. It’s not a good thing. It means that your airway is closed or partially closed.

So, that’s how it came about.

From there, it was learning the system. How do you get treated for this? How do you get diagnosed? What does it actually mean? And it was a long journey. It was a long process for us.

And that’s what prompted me to write the book. It was a very frustrating process. There were a lot of roadblocks and a lot of things that had to be learned and unlearned to accomplish a good, satisfying end point of success and efficacy. It literally took us probably a year or two to figure it all out.

And both my wife and I are healthcare professionals! It was a little concerning to us that we didn’t know what needed to be known and nobody else did either. We went to our primary care physician, we didn’t get much help there. And so, like many people do, we had to go online.

Unlearning What We’ve Learned about Sleep

Maureen: So, what did you have to unlearn about sleep? For the common folks, what do we think is true that you found is not after all?

Dr. B: Well, I talked about this in my book a lot, The 8-Hour Sleep Paradox, the myths around sleep apnea. I was in great shape. I could mountain bike six hours straight. I could do 7000 vertical feet of climbing literally on a bike. And we would bicycle to the top of the White Mountain—that’s 14,000 ft., 35 miles—and we felt great! And we felt our sleep was great.

So, when that man leaned over at breakfast and said, “Listen, that’s serious. You should get help,” I felt I didn’t fit that stereotype of the large, Big Mac overweight, older male.

And my wife’s petite. She’s 5”4 and weighs 120 lbs. As it turns out, she was the one snoring louder than I was. Apparently, you can be thin and female and have sleep apnea. That’s something we learned later in our sleep studies.

Maureen: But you never thought there was a problem with that?

Dr. B: Never!

Maureen: We sort of accept that, that some people snore and that’s not a big deal.

Dr. B: Right! And of course, if we’re sleeping, and we’re in that in-between state of deep sleep and light sleep, we have no idea what’s going on. We’re not rational. We’re not thinking and analyzing things. That’s impossible!

That is one of the paradoxes of sleep. You really can’t measure or think or discuss what your sleep quality is. We all say, “Oh, I sleep fine. I sleep like a baby. When I hit the bed, I’m out like a light.” Well, it turns out, that’s actually a bad thing. If you go to sleep in under a few minutes, you’re tired.

Maureen: You’re really tired.

Maureen: We wear that as a badge of honor. My wife would brag to everyone on a plane, on a train, a car, “No problem! I can be out and still get a quick cat nap in.” Well now, we’re kind of boring because we can’t take cat naps anymore. We’re wide awake.

So, those were the things that we had to undo in our mind. And that’s what I educate people on every day.

In fact, someone told me an hour ago, “Oh, I fall asleep right away.” I had to back them off and say, “Listen, let’s talk about that. That’s called sleep latency. We have a word for it. We define it. We measure it in a sleep study, the PSG (polysomnography). And here are the different categories… it should take 12 to 15 minutes to go to sleep.”

And I remember making that transition from falling asleep right away to taking 12 to 15 minutes to go to sleep. It does take me 10 to 12 minutes. If I’m out like a light, I get worried. Right away, I try to analyze what’s that about. Was it because I went to bed too late? Is my Circadian rhythm off? Do I maybe have a sinus infection? Or am I mouth breathing?

I didn’t know any of that. It wasn’t taught in dental school. I didn’t get that in any continuing education classes. So, a lot had to be learned, re-learned and even unlearned.

Sleep Disturbances

Maureen: Now, I’m imagining that when you have apnea, you keep getting woken. You have this obstruction, and you keep getting woken. That probably affects your brain a lot.

Dr. B: It can affect the brain in many different ways. The most obvious thing is that it prevents you from going into that deep sleep.

Deep sleep is when we repair the brain. That’s when the brain shrinks a little bit and the glial lymphatic system starts draining all the toxins in the brain.

And another theory is that memory consolidation occurs in deep sleep. There’s no brain damage that occurs. The brain is fixing itself during that time.

If every time you approach that state of deep sleep, you keep bouncing out of it, well, you’re missing out on that reparative process.

AHI or the apnea-hypopnea index is a measure of how many apneas or hypoapneas we experience in an hour of sleep. It tells us the number of low breaths/no breaths per hour. And to a lot of people, when we start seeing 5 within an hour, that’s when we start getting concerned.

A lot of people are like, “Well, I don’t see that as a problem. I get 15 or 20 of those, and I feel fine.” Right away, that’s an indication that there’s something going on and they have a worse state of sleep apnea than they thought.

For myself, I know now what a good night’s sleep is—when I thought I did before. I went from 12 apneas to 0 apneas with the use of an oral appliance. My wife, after surgery—and she’s using an oral appliance herself as well—she went from 34 ½ apneas to 0 apneas.

And this, by the way, is being measured by an objective polysomnograph. This is a test done at a sleep clinic. And we do that to verify that the device we’re using is actually working.

And so, the difference between 12 and 0 apneas or interruptions per hour is significant. It is amazing! The next day is better. You get up earlier. You don’t wake up in the middle of the night. You wake up before the alarm goes off. You don’t have that headache or that sense of dread, “Oh, my God! If I could just sleep another half hour” or “Oh, no! The alarm’s going off in 10. I’ve only got 10 more minutes.”

With my wife, it was, “How soon can I get my coffee?” It’s not a pleasant thought to wake up to every morning. You should wake up refreshed and happy.

Behavioral and Psychological Aspects of Sleep Disturbances

Dr. B: And there are other reasons why you may be a little anxious when you wake up in the morning. And that’s the behavioral, psychological part of interrupted sleep.

Maureen: Oh, tell us about that. That’s a new thing.

Dr. B: That is something I like to talk about a lot because it doesn’t get talked about enough I think. And that is the anxiety of light sleep.

Now, I’m not talking about insomnia—although that certainly is very anxiety-producing—but it’s a person who thinks he’s sleeping well, but has actually been having restless sleep. They’ve been tossing and turning. They never really reached the deep state of sleep. They never really were able to get into REM sleep for long enough. They weren’t dreaming. That memory consolidation didn’t occur. The brain didn’t cleanse itself. They didn’t really sit there paralyzed for long enough for that physical rest. There’s a host of other things that happens during deep sleep that we’re not aware of.

We really don’t know to this day why we sleep; we only have theories.

For instance, the fight-or-flight response of choking at night because the muscles are collapsing, imagine that happening. I have patients who has 70 AHI’s an hour. They’re gasping, and they feel like they’re dying. That’s just the subconscious mind picking that up, but it does filter through.

People that start sleeping well start feeling better. There is a connection between depression, mood, anxiety, mood disorders, and disturbed sleep. And that’s the behavioral part of it.

Think of this. If someone was sitting next to you while you’re sleeping, and kept poking you with a little sharp instrument, and you said “ouch” 12 times an hour, how would you feel in the morning?

Maureen: Horrible!

Dr. B: It’s like an all-nighter! When you stay up until 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning, you know how you’re going to feel.

And sleeping in light doesn’t help either. Having that extra sleep is meaningful.

So, sleep pretty much trumps everything. Think about it. We can survive without food and water for longer than three days. They’ve demonstrated this with people. After three days of no sleep at all, you pretty much lose your mind.

Maureen: Yeah, I understand that it’s really important for mental health. And it’s one of the predecessors, a lot of times, to psychotic breaks—that lack of sleep for multiple days.

The Myth Behind BMI and Obstructive Sleep Disorders

Maureen: You had said something about how, usually, we don’t suspect that there could be any problem with apnea (or other obstructive breathing disorders) with petite women. Can you tell us about that?

Dr. B: That’s another myth around sleep apnea. A lot of very fit, young to middle-aged, pre-menopausal women think that they’re immune to sleep apnea because they don’t fit that stereotype of the large-necked, overweight male. But in fact, they actually can have very small airways because they are petite.

Now, it doesn’t necessarily follow that if have a small dress size, you’d have a small airway. It’s not that kind of a correlation. It just is a known compromise in the human body.

You don’t have to be overweight (though that can certainly aggravate sleep apnea). You can be of any body type and still have that compromised airway.

And so, a lot of women exhibit it differently. It’s a condition called UARS, Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome.

I’ve had a conversation about that this morning with a new patient that was describing his wife’s sleep patterns. She’s very thin and very fit. She was pre-menopausal. And she’s had one child. She’s beginning to snore a little bit, making little gurgling noises. It’s not a full-on snore. The airway doesn’t close completely, but it’s restricted enough where it produces an awakening event and a disturbance in her sleep.

And that’s because the airway is narrow and small. She can’t get the air through.

And then, women of course do catch up with men at menopause for a variety of reasons. They start having those full-on sleep apnea signs and symptoms—the snoring, the tossing and turning, the day time tiredness and all that.

There was a study done out of Sweden. I’m not sure when, but it was probably about 10 years ago. They took the healthiest, fittest, youngest, pre-menopausal, lowest BMI women they could find. And of those women, 49% had UARS.

Maureen: Why is that? Why is that so prevalent?

Dr. B: That is a very good question. And we have lots of explanations.

It could be the way we’re developing. It could be epigenetic factors. It could be our environment.

I mean, we don’t evolve as quickly as we do epigenetically. So, in one generation, you can have issues with the airway—mouth breathing as opposed to nose breathing due to an allergy to a food, something that’s been introduced that we have not yet evolved to be able to handle, or it could even be air pollution.

There are some dentists, physicians and orthodontists that believe we’re not developing properly. The development of our lower face is not reaching its genetic potential. If the width of our upper jaw bone, the pterygoids (the back part where the second molars are) doesn’t grow to the proper width, the passageway (that little aperture in the palate where post-nasal drains into at the back of the soft palate) becomes very narrow, and then that restricts breathing. We become more mouth breathing biased, and we do nasal breathing. That has its effects in development.

It’s like when we came off the shores on all four legs, and then decided to become upright. Our knees were challenged, our lower back was challenged—and our airways were challenged! We had to bend the airway. It’s a kink as we became upright. That produced a smaller airway as a compromise.

There’s also our voice box. Over time, as we became more linguistically capable, the voice box moved up. And then, of course, the trachea is there. And that’s where the lungs and the airway had to differentiate what’s air and what’s food.

So, there’s a lot of stuff going on there. And it’s complicated.

And then, of course, if we gain weight because we’re eating a western diet and shopping in the middle shelves of our grocery stores for crackers, packaged foods and all that stuff, then you can get a marbling of the tone. You can gain fat in the tone. You can gain fat in the airway.

And then, as we get older, the muscles do lose their tone. These muscles have tone. That’s why we’re able to breathe better during the day than we are during REM sleep. It’s because those muscles are then paralyzed.

We don’t know a lot about it. We think we’ve got a handle on it, and we have our theories, but it’s a multi-factorial perfect storm of things that are not going well.

So, that’s why a lot of these women have UARS. Maybe it’s been that way all along and maybe we’re just better at measuring it now. That could be part of the equation certainly.

Getting Sleep Studies

Maureen: And so, you have to have a sleep study to understand whether or not you have UARS, correct?

Dr. B: Right! Yes, right.

And sometimes, a sleep study will not pick up UARS. It depends on how well it’s administered and whether it’s got all the channels that pick up that sort of thing. Sometimes, the person that’s reading the sleep study doesn’t pick it up. It’s very subtle. But apneas can be picked up on a PSG.

But I’m all for testing everyone for sleep starting at age one. And I know that’s a a tall order. And financially, the actuaries are looking at that going, “Oh, my God! This guy is crazy!” But think of the money it would save down the road. I mean, we’re talking about billions of dollars! The effects of sleep apneas from car accidents to industrial accidents, I’ve seen costs all the way up to $500, $600 billion or $800 billion associated with that. So, certainly, it would be less of a financial load on our very crazy healthcare system that’s going through all sorts of cost overruns.

And the same thing with Alzheimer’s numbers. I read somewhere the other day that if we could delay Alzheimer’s by five years in our aging population, that’s a saving of $365 billion. I would relate that back to sleep. I would say if we can just make sure that everyone sleeps well and properly at a young age, then that would be a delay of 10 years perhaps or even 20 years. That would save money.

Maureen: Right! And you don’t have these major accidents that we have. We don’t have to have these oil ship cruisers running into things and planes going down and all these things.

Dr. B: One of the classic accidents that they refer to in sleep studies is called the Selby incident. It was a man who was under the care of a physician for sleep apnea. And at the time of the accident, he wasn’t wearing a CPAP. He drove his Range Rover and it crashed because he fell asleep on the wheel. It flipped, and it landed on the tracks of a commuter train, and it took down a whole commuter train. People died.

So, when you think, “Oh, well, I don’t have a CPAP, and it doesn’t affect me,” it can affect you. You may not have sleep apnea. You may be from that 60% or 70% of the population that doesn’t have the sleep apnea. But one day, when you or maybe your kid is driving down a one-way road, someone could run into you and cause harm to you.

There was a commuter train in Manhattan recently, in the Bronx. And later, it was decided that it was not texting that was the root of that accident. It was undiagnosed and untreated sleep apnea. The poor man fell asleep, and he came around the turn too fast.

Maureen: Oh, shoot! So, can we get these studies readily? What does it take to get a study? And where can we find them? Are they in most cities?

Dr. B: So, the PSG is the standard of care. It’s the gold standard. It checks for brain wave patterns. It can identify deep sleep through brain wave patterns. That’s probably the best way to do that. It can also measure air velocity through the nose and mouth, and it can record snoring.

Some PSG’s have a camera that are looking at movement and periodic lung movement. You can actually get that with little attachments, little sensors on your legs. They’re monitoring heart rhythms because, usually, there’s a rise in the blood pressure and the heart rhythm before the apneas.

So, all that’s being recorded. And that’s a lot of information. The problem is that, sometimes, it’s so much information that you really have to have someone who’s very skilled at reading that to score it properly. But right now, that’s the best.

Is that available everywhere in the US? Pretty much, unless you’re in a very rural area. Hopefully, your primary care physician would diagnose it, then they would just send you maybe to a long car ride to a larger metropolitan hospital that would have it.

But you can also get home studies. You can get a PSG that’s pretty good in your own bed. It’s the perfect thing you can do.

But here’s the thing. That PSG is pretty much of a roadblock in some cases because the insurance companies don’t want to pay for it. Some of the physicians in large group dental practices, PPO’s and HMO’s are incentivized not to prescribe it.

For example, if you’re a healthy, fit, thin, premenopausal woman, with no symptomology other than maybe “I’m a little tired during the day,” maybe they would be prescribing you an anti-depressant instead.

Maureen: Right! They’re cheaper.

Dr. B: Exactly! So, those people, unfortunately, fall under the radar. They’re not getting their PSG’s.

And that’s one of the reasons I wrote the book. I was very frustrated. I learned how to recognize sleep apnea decades before a physician could typically.

And because of unique things in the mouth that are available for me to see (I saw this in my patients, and then I learned how to recognize all the other symptoms, i.e. the day time tiredness and sleep latency and things like that), I would refer them to their primary care physician only for them to be turned away. They would basically be contradicting me saying, “Oh, he/she doesn’t think I have sleep apnea.”

Well, I would push a little harder. I would get them the sleep study.

More recently, I have re-routed that system. I route now to a sleep clinic directly. And pretty much everyone comes back with their own scale of sleep apnea. Once I suspect someone as maybe having UARS, or if we’re not sure, we just march them along. But it’s easy to diagnose this.

Now, legally, I cannot diagnose this. I can only screen for it. And that’s in fact what I do.

But when I send that out to a primary care physician, I want them to do the sleep study.

Maureen: And so, it seems as though the situation you’re in now is unique in that you are going straight to a sleep clinic.

If they went to their dentist, and they asked their dentist, can you figure out if I have the likelihood of having, the traditional dentist wouldn’t know what to look for…

Dr. B: True, unless they were trained via AADSM. You could go to AADSM.org. They have a list of dentists that are trained in this area—and it’s a growing list. It’s the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine.

Maureen: So, they need a sleep dentist who understands what they can look for, and then they usually have to refer to the MD because the MD can do the diagnosis and the prescription for the sleep apnea study actually.

Dr. B: That’s right.

Maureen: So, it might be a little frustrating for people, but they can at least try to get this study done.

How to Find Out If You Have Sleep Apnea Without a Sleep Study

Maureen: And if they can’t get a study done, is there anything people can do on their own if they just have this sense that maybe they have apnea? Maybe they’re looking to get the test, but they’re running against the wall?

Dr. B: That’s a very good question. There are apps on smart phones. That phone will record you at night. It will tell you what you’re not getting because you’re asleep. It will tell you what happened at night, and it will give it to you in a condensed form.

It only plays back what it heard. And it will quantify it for you. It’ll tell you how many interruptions there were. And that would be a snoring event or a rolling over event. And that’s useful information.

There is a new technology coming, something I’ve been kind of wanting for a long time. And I’ve talked about it the book. It’s kind of an everyman’s sleep study. And that is coming.

I’m actually a medical advisor for a company in San Francisco that is about to launch a new product. And I can’t say too much about it at this point in time. But it’s KnitHealth.com.

It’s a touchless system. It can actually witness the apneas and hypopneas and UARS and mouth-breathing as opposed to nose-breathing without touching you. It’s very inexpensive. And it’s portable. You can put this any place you sleep—in your tent at night if you’re camping.

So, that is very promising. I think, soon, we’ll have something where everyone can test not only if they have sleep apnea, but verify if their sleep solutions are working

Why not know every night? Why not have a mattress or a machine tell us “that was a good night sleep. We got an 87%. The night before, it was a 62%,” and then average that over the month?

We have that technology. We should be able to get that information.

Maureen: And then, like you said, you can correlate it. You get this information and it says, “Oh, you didn’t sleep all that well last night,” and you could start to think about what you did yesterday and what were the factors that you can control in getting yourself a better night’s sleep.

Dr. B: Right! That software is coming, a smart software that basically will tell you, “You know what? The reason you did that is because you had a little too much alcohol too close to bedtime… and you went to bed 45 minutes later than you normally do, and you slept in a little bit. So the next time, your sleep will be affected.”

That will come. I mean, it’s here already, but it’s not mainstream. And it will be incorporated into devices that will actually help us sleep.

CPAP Machines & Other Sleep Solutions

Maureen: So then now, when you have apnea or maybe other obstructive sleep disorders, you have to have a CPAP machine. What are the other options that we might have to be able to deal with it?

Dr. B: So, the gold standard still is the CPAP or the APAP. And that’s basically, in very simple terms, a machine that blows air past your airway, up against your airway, through your mouth and nose. It’s a simple device. It keeps a lot of pressure in there so that it does not collapse.

You know how you have those little bouncy houses? You’ve got that little fan going all the time. That’s what the CPAP is doing. It’s keeping up the little bouncy house.

And that sounds terrible, doesn’t it? But they do work.

It’s not a very refined way of doing it. And also, the way it’s delivered is not very refined. A lot of people are just handed this machine and are then expected to figure it out on their own. And it is a very difficult machine to learn how to use. So, compliance is very, very low—30% probably after the first year.

And then, there’s no follow-up. People will give up! They say, “I can’t do that. And if I can’t do that, then I’m just going to do the best I can.” Again, sleep apnea is not a definitive thing where you know you’re dying right away. It’s a very slow progression of things. So you just stand back and say, “You know what? I’m doing pretty well. I’m just going to go with the flow and not work with the CPAP.”

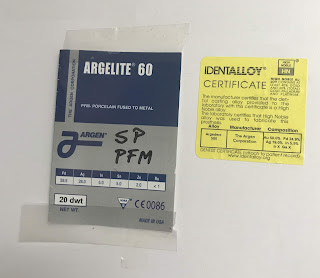

The other method of dealing with the airway and preventing it from collapsing is that oral appliance or the mandibular advancement device. And that’s in the realm of dentists. That’s something that we can prescribe.

That works well. I sleep with one. That’s what brought me from 12 to 0. That’s what brought my wife from 3 or 4 to 0. But they don’t work for everyone. I consider it to be a second line of defense.

I think the two together, the CPAP and the oral appliance, in severe cases (or even in moderate cases) are optimal. I think that should be the gold standard. Why push up against something that you know you can move out of the way, like the base of the tongue up against oropharynx? Why not open that up a little bit, turn down the pressure of that pump, and let it run at a slower rate? It’s much more comfortable at lower pressures.

So, I think the two together are fine. I’ve done a lot of that. It’s called hybrid or combination therapy. And that seems to work very, very well.

Now, of course, the last method would be surgery. And that I think should be a last resort. The classic surgery for this, which I think is falling out of favor, is the UPPP surgery. That has a checkered past.

It works 50% of the time after the first year. Scar tissue can build up. It’s very painful. You’re out for four to six weeks. And it doesn’t always work.

Although there are some very skilled surgeons, I have to say, that have modified that and are getting some success. But again, that should be a last resort.

And weight loss helps too. If you can get that airway a little bit bigger by losing some of that fat in the airway in the base of the tongue, that would help too.

But ironically, it takes good sleep to be able to resist all those carbohydrates and all those little goodies in the center aisles of our grocery stores. Your cravings for those are very, very high because you’re looking for energy. So, it’s a complicated thing.

That’s why I wrote the book. I tried to simplify it. It’s almost like a manual. And we tried to make it as enjoyable to read as possible.

The 8-Hour Sleep Paradox

Maureen: Well, why don’t you tell us about your book, The 8-Hour Sleep Paradox? Tell us where we can find this.

Dr. B: Well, it refers to the paradox of being told that all we need is eight hours of sleep. I’ve always had a problem with that.

Eight hours is a great period of time to sleep. Some say it’s 6 ½ to 7; some say it’s longer. And then there’s also the 2-stage sleep where you wake up at around midnight, make a fire, look at the stars, and go back to sleep. I forgot what that was called, but there was a UCLA study that talked about that.

But anyway, it’s not about the time. It’s about the quality of the sleep. That’s what the conversation needs to be about. Are we getting good quality sleep so that eight hours is actually good enough?

So that’s the premise of the book.

And of course, we also tried to demystify a lot of things. I wrote it with my daughter who also has sleep apnea. She’s young, but we caught it early. And thank goodness that we did! She sleeps with an oral appliance.

And now, she’s pregnant. My grandchild might have sleep apnea, who knows, right? But these things need to be addressed early on. That’s really the only way we can do this, by being aware of it.

So, we simplified the book. I threw a lot of nerdy stuff in there. My daughter, as a layperson, was wonderful. She would bounce back at me and say, “Dad, why… and when?” It was a collaborative affair for about a year.

And it’s been well-received because it is easy to read. It gives people actual items. And that’s exactly what we wanted to do. We wanted to demystify the process.

Remember, my wife and I are healthcare professionals. And we don’t get it! No one was guiding us. We’ve made a lot of wrong turns and a lot of bad decisions. And so, we wanted to prevent that from happening.

And of course, I saw this too with my patients directly. In my mind, I needed a protocol. And that’s what I was developing that then got translated right into the book.

So, it’s a self-help manual. I think it’s one of the best self-help manuals out there. There are plenty of them out there, and the last thing we need is another one. But this one’s on a very basic, primal level. It’s all about sleep.

And again, if you don’t get deep sleep, everything else is going to falter regardless of whether you have the best diet in the world or if you’re exercising every day. You’ve got to have that frame of mind that comes from deep sleep, and that is you’re motivated, you’re self-actualized, you’re happy.

And when things do go wrong in your life, you can deal with it. Rest is more manageable. We all have stress, that’ sinevitable.

But lack of sleep, I see this all day long in my practice. And people are handicapped, they really are handicapped. They’ve lost control of their destiny by not being able to know more about their sleep and verify their sleep.

And so, really, from a very basic point of view, it came from that.

Maureen: Well, that’s terrific. So, people can get this manual to help themselves, and like you said, be guided through the steps—how to, first of all, figure out whether they need a sleep study (you believe everyone does), and if they’re going to try to get one, how would they go about doing that? And there’s also a quiz in there and all the questions to ask.

Dr. B: And there are lots of bullet points, so that when you read through it, you can just check them off and bring it to your doctors and say, “Listen, I got 70% of these. I have GERD, I’m overweight, and I’m not sleeping well. Can you do something for me?” I mean, it’s that simple.

Maureen: And please don’t give me a PPI and tell me to go away.

Dr. B: Exactly, exactly.

Maureen: Okay! Well, terrific! Thank you very much.

Final Thoughts

Maureen: Are there any last things you want to leave with our audience before I let you go?

Dr. B: No! I mean, we’ve talked about a lot, but I would say verify your sleep. Make sure that you’re a good sleeper. And if not, then deal with that.

And this goes for your loved ones too. If you see someone suffering, snoring, or they’re not sleeping well, do something about it. There are simple solutions. And it improves the rest of your life.

Maureen: Great words of wisdom! Well, thank you, Dr. B. I appreciate you being on the summit.

Until next time, love yourself… take care of yourself… and stay sharp!

The post What Women Need to Know About Sleep Apnea and Brain Health (Interview) appeared first on Ask the Dentist.

from Ask the Dentist https://askthedentist.com/sleep-apnea-and-brain-health/

Comments

Post a Comment